Rolling with the Times: How Mobile Services Innovated During COVID

Fold-out screens, video games, and dressed-up designs are just some ways that libraries safely updated their mobile services while preparing for summer 2021.

|

The Madison (OH) Public Library vehicle, slated for an update with an eight-foot screen and other equipment.Photo courtesy of Madison Public Library |

Ice cream trucks will face stiff competition in Madison, OH, this summer, when an irresistible bookmobile makes its rounds and attracts kids. The revamped vehicle will have an eight-footinflatable screen and video console on the outside, where young people can safely play games.

In Missouri, a bookmobile will draw patrons another way: with a giant illustration of a child and dog reading, by local author and artist Mary Engelbreit, wrapped around the 40-foot-long trailer truck as it travels the 523 square miles of St. Louis County. And in Evergreen Park, IL, Trike-a-Delic, a tie-dye–painted, three-wheeled book cart, will make its maiden voyage this month.

Those are just a few ways that the more than 500 U.S. public libraries that operate 800-plus bookmobiles are reconnecting with communities and sparking excitement among children and teens whose chances of fun have been severely narrowed due to COVID.

“It’s really made people reimagine how to get books into the hands of children and continue to promote libraries and literacy and books,” says David Kelsey, president of the 400-member Association of Bookmobiles and Outreach Services (ABOS), an American Library Association affiliate.

But in many places, these plans are built on optimism tempered by the unknown: Libraries have created a wish list of in-the-field programming, with virtual versions as backups.

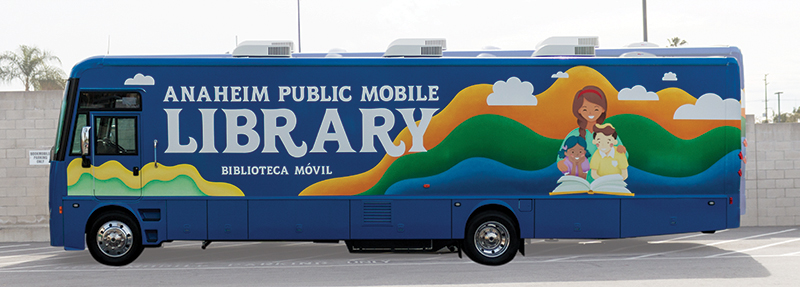

“It’s COVID; everything is different. This summer will be different from last summer, even,” says Katrina Ford, senior librarian at the Central Library in Anaheim, CA. “A lot of things are up in the air right now.” Three of Anaheim’s seven libraries have reopened, but they are still waiting for clearance to allow people into the 38.5-foot-long bookmobile that holds about 5,000 volumes. Ford is eager for things to return to normal, or “normal-ish,” as she puts it. Before COVID, 40,000 patrons, mostly kids and teens, visited the bookmobile each year.

Anaheim will inaugurate a new vehicle this summer that is not designed to be boarded. The 16-foot Dodge Ram ProMaster will house the library’s grant-funded STEAM Adventures: Exploration on Wheels program. It will stop at parks, libraries, and community centers, carrying supplies for science, technology, engineering, art, and math projects. A large LCD monitor that swings out will broadcast a library STEAM team member leading children through an experiment or exploration. Kids who can’t get to the site can pick up the kits at their local branch and follow along from home on Zoom.

The Fountaindale Public Library District (FPL) in Bolingbrook, IL, allows one person or family at a time into its bookmobile and requires them to wear masks. But it’s not an adequate solution for the more than 75,000 residents of this Chicago suburb. Prior to the pandemic, the bookmobile attracted as many as 200 children and their parents when it set up for puppet shows, sing-alongs, story time, and book talks in local parks. When the pandemic hit, the library recorded the programming and uploaded it to its YouTube channel.

As for live summer events, well, “I wish I knew that myself,” says Tana Petrov, FPL outreach services manager. For now, staff are continuing to record the activities, but they have also ordered a new bookmobile with a large external video monitor. They hope to drive it to underserved communities for families to watch some of the programs outside, giving them space to maintain a safe six-foot distance.

The Livingston Parish (LA) Public Library has similarly adapted. “I’m a people person, so I love being out and about, going to see different things and meeting different people and helping the kids,” says outreach services coordinator Michelle Parrish during a phone call from the bookmobile.

But since COVID, no one has been allowed inside the vehicle. Instead, Parrish and her assistant drop off craft supplies related to children’s books read on the library’s YouTube site. Much of the 648 square miles covered by the bookmobile is rural, and single parents in particular often do not have the time or even a car to travel to the nearest library branch, Parrish says. She hopes to return to some traditional outdoor summer activities and bring the bookmobile to gumbo festivals, day care centers, and summer camps run by the parks department.

Getting the books out

When COVID forced school districts in southwest Maine to cancel their annual K–12 student art show, the Tri-Town Bookmobile stepped in and displayed the artwork on both sides of its 40 feet of windows. The Bookmobile, a converted school bus, was created in 2017, through a collaboration of the town libraries of Berwick, North Berwick, and Lebanon; the school district; and the adult education system, to address low literacy rates, food insecurity, and housing insecurity in a remote, rural region stretching from the New Hampshire border to the Atlantic coast.

Kindergarten screening scores indicate that many students enter local schools with reading levels typical of a three-year-old, and half the high school junior class fell below proficient in reading, according to literacy screenings administered over the past two years.

“It is painfully clear that our students and their families are not reading enough. Reading is not a strong enough part of the cultural fabric of our communities,” says Laura Cashell, project coordinator of the Bookmobile.

The bus gets kids fired up about books. “[Kids] get very excited when they see the big blue book bus driving down the road,” says Cashell.

Cashell shared ideas about reconceiving bookmobile activities during COVID at the 2020 ABOS conference. (The organization is also hosting a “Virtual Bookmobile Parade” on April 7.) She suggested that bookmobile staff offer literacy outreach programming for families unable to access traditional summer programs—such as parks and rec camps and enrichment programs run by nonprofit community groups that provide reading instruction.

For now, Cashell says the library plans to offer story time at parks and require masks and social distancing, and may run some outdoor STEM activities. Until the CDC eases COVID safety recommendations, all other stops, such as day care centers, food distribution sites, farmers markets, and sports events, will be curbside service only.

Where the magic happens

Bringing books and other library services to rural communities is one of the two main purposes served by U.S. bookmobiles, says Jessa Lingel, associate professor in the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania. The other piece is to reach people who wouldn’t normally come to the library, such as immigrant populations “who don’t necessarily feel that the library is for them,” says Lingel. “Bookmobiles often become a tool of bringing people in, less in a geographic sense than in a cultural sense or a political one.”

Zoom and YouTube can’t replicate that outreach. Taking the library virtual is fine as a COVID contingency, but librarians say that the in-person connection of a bookmobile is where the magic occurs. “I’ve seen lives transformed,” says Ford.

|

Anaheim Public Library’s bookmobile holds 5,000 volumes.Photo courtesy of Anaheim Public Library |

Keely Hall, Anaheim Public Library principal librarian who oversees bookmobile operations, says that some uplifting interactions occur in neighborhoods known for gang activity. Residents like the bookmobile, she says, because it brings something positive into the community. Patrons participate in reading, crafts, and story time with their kids, says Ford.

The library is waiting on approval for an effort to head a mobile city service outreach program, according to Hall. The bookmobile would be the anchor, and city services would set up tables providing assistance on services, including helping residents register for COVID vaccines, providing information on registering for WIC, emergency rental assistance and utility payment assistance, and other economic assistance programs.

In February, Ohio’s Madison Public Library received a grant from the Association for Library Service to Children to transform a Bluebird school bus into a rolling video game arcade, with an inflatable screen and video console on the side.

“We’ll have lights and sound and plenty of noise to draw people in,” along with snacks and big signs, says Shawn Walsh, emerging services and technology librarian. Kids will be able to choose from Fortnite and Minecraft, selected for their tie-in with graphic novels, purchased with grant money.

The bookmobile drivers, also athletic coaches, thought up the idea when the library put the bookmobile back on the road in late spring, visiting neighborhoods and mobile parks. One person at a time could enter, and while the drivers were waiting, kids would tell them, “Well, I don’t read.”

“Do you play Fortnite?” the drivers asked. “Did you know that we have Fortnite books?” The kids would leave with books.

The St. Louis County Library has four truck and trailer bookmobiles, each with a decorative wrap, from Engelbreit’s illustration to the library’s new owl logo, and capable of holding up to 10,000 books. During the school year, they visit all 60 schools. They still visit those with in-person learning, and access is restricted to four children and two adults at a time. Like many bookmobiles, they also provide hot spots, so anyone nearby can access the internet, and tablets for folks to borrow while using the hot spots.

The plan is to put them on the road this summer, says Crystal Harris, manager of bookmobiles and mobile services for the county libraries and an ABOS board member, and visit schools holding summer classes, local parks, and summer camps. The library is also partnering with the County Health Department to get face masks to give out for free. Harris is a fan of giveaways. Kids who return all their books get a library bookmark. The vehicle also carries pens, pencils, and other small gifts for children celebrating birthdays.

A smaller bookmobile, Sweet Reads, carries donated books that kids can keep. Sweet Reads has a simple goal, says Harris: “To make sure children have books.”

Smaller presence, big impact

|

Denver Public Library’s Wheelie has been dressed up as a spider, a UFO, and a unicorn.Photos courtesy of Denver Public Library |

Denver Public Library (DPL) is part of another mobile services trend: taking a step back from bells and whistles. For the past five years, DPL has been pedaling Wheelie, a 150-pound, teardrop-shaped trailer that holds about 150 books, into downtown neighborhoods to distribute its books and library craft kits. All are given away for free.

When COVID hit, the library took its traditional bookmobile to food banks, homeless encampments, and other places where people in need were accessing resources, and Wheelie made pilot visits to those locations. The process was as low-touch as it was low-tech, says library outreach specialist Mikel Stone, an avid cyclist and Wheelie rider. Staff laid books on the ground arranged by reading levels, and parents and children selected what they wanted.

This summer, DPL plans to do more, especially because the encampments are now more spread out. The library is also receiving requests from community partners for Wheelie to attend events. Since Wheelie is more flexible than its behemoth bookmobile bretheren, it can go into smaller neighborhood parks and inside places that would not allow a motorized vehicle, such as the Colorado Convention Center.

Library staff enjoy sending Wheelie out in costume for special occasions. It has been dressed as a spooky spider, a lit-up UFO, a sparkly unicorn, and Ms. Pac-Man, and it rode in a Halloween parade as ghosts from Pac-Man. Its diminutive size also brings a smaller price tag: Wheelie was manufactured by the Burgeon Group (which has since stopped making them), at a cost of $10,000; the average bookmobile is closer to $200,000.

|

Evergreen Park (IL) Public Library’s unique Trike-a-Delic.Photo courtesy of Evergreen Public Library |

The summer of 2021 will mark the inauguration of the Evergreen Park (IL) Public Library’s Trike-a-Delic, a book bike named for its tie-dyed wrap designed by Jenna Harte-Wisniewski, head of adult services at the library, and staff. “I wanted something eye-catching,” says Harte-Wisniewski. “The first thing that came to mind was tie-dye, because I feel like I’m a hippie at heart.” Trike-a-Delic will carry an iPad and a Wi-Fi hot spot so librarians can do library card sign-ups.

Trike-a-Delic was made by Icicle Tricycles, based in Portland, OR. At 120 pounds, it’s heavier than the teardrop design, but is less than half the price. It also comes fully assembled and has seven gears to handle hilly challenges.

Whether they’re on three wheels or a trailer truck, providing remote programming or following COVID-safe practices to get kids inside, there’s one overarching mandate for a successful bookmobile, but especially this summer: It has to be fun.

“My goal as the manager, and I tell this to everyone that we hire, is that we are trying to give these children a positive bookmobile experience,” says Harris from St. Louis County Library. “We’re not worried about how loud they get, we’re not worried about how overly excited they might be. When we are here, we want them to walk away from the bookmobile excited and ready to come back at the next visit.”

Kathryn Baron is an education reporter based in California.

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!