The Schneider Award Turns 20

Authors, committee members, and Katherine Schneider herself reflect on how the Schneider Family Book Award has propelled disability representation into the spotlight.

Growing up, Katherine Schneider struggled to find accessible books, not to mention ones with decent disability representation. Blind since birth, Schneider was the first child who was blind to attend Kalamazoo, MI, public schools. A librarian at the Michigan Library for the Blind supplied her with books in braille. Schneider was valedictorian of her high school class in 1967.

|

Katherine SchneiderCourtesy of Katherine Schneider |

When her father passed away in 2002, Schneider, a clinical psychologist and university professor, wanted to use her inheritance to create an award related to disability representation in children’s books. She cold-called the American Library Association (ALA) until she reached Cheryl Malden, ALA’s program officer. Schneider described her idea, which was modeled after the Coretta Scott King Book Awards, established in 1969, but with a disability focus. Malden immediately understood the award’s potential.

That’s when the Schneider Family Book Award became more than an idea.

This year marks the 20th anniversary of the award, which honors “an author or illustrator for a book that embodies an

artistic expression of the disability experience for child and adolescent audiences.”

In those 20 years, the Schneider Award has evolved from a little-known prize with few annual submissions to one that gains relevance every year in a field with expanding representations of disabilities. Three winners in teen, middle school, and children’s book categories receive $5,000 each (split between author and illustrator for graphic novels and picture books). In 2019, the committee added one to two honor books in each category. This year’s choices will be revealed at the live streamed Youth Media Award announcements on January 22.

But back in 2004—the first year the award was given—even the winners were unaware of it. Wendy Mass, author of that year’s winning middle grade novel, A Mango-Shaped Space, remembers the day well. A former children’s book editor at Longmeadow Press, Mass was watching the Youth Media Award announcements from home out of curiosity. Like that year’s other winners—Andrew Clements, YA winner for Things Not Seen, and Glenna Lang, for Looking Out for Sarah in the picture book category—she didn’t know there was a new prize celebrating disability.

Watching with a dial-up internet connection, Mass had trouble hearing the announcements. Ten minutes after the ceremony, an excited representative from her publisher called her from the convention floor saying that her novel, about a girl with synesthesia, had won the new award.

For Mass, the thrill is still tangible. “I was so honored! It was all so exciting.”

[Also read: "The Printz Grows Up: High Points in the History of an Influential Award"]

Mass has since published dozens of books, but A Mango-Shaped Space is still her best-selling work, she says. Over the years, libraries, schools, and readers have also benefited from the Schneider by having a dedicated list of stellar books with disability representation to buy and read.

Lang, whose book Looking Out for Sarah is told from the perspective of a guide dog for a musician and teacher who is blind, remembers her 2004 win as a surreal event. “The experience of winning the award was really kind of supernatural, like an out-of-body experience,” she recalls.

Far beyond those initial feelings of euphoria and validation, the award produces long-lasting benefits for recipients, who see a bump in book sales immediately after the award and for years ahead.

That was true for 2023 winner Shannon Stocker, who knew her picture book biography Listen: How Evelyn Glennie, a Deaf Girl, Changed Percussion, illustrated by Devon Holzwarth, was up for consideration. When Stocker received a call on a Sunday night last January from a Schneider committee member, she shouted for her family and put the phone on speaker. The committee member informed them that Listen had won, and Stocker burst into tears.

“As much as you hope something like that might come to fruition, it just seems like such a dream,” she says. “You don’t actually expect it to.”

|

From left: 2023 committee cochairs Susan Hess and Mary-Kate Sableski; Right (Left to right): Agent Nicole Tugeau, 2023 illustrator winner Devon Holzwarth, editor Jess Garrison, 2023 winning author Shannon Stocker, and agent Allison Remcheck.From left: Courtesy of Susan Hess; courtesy of Shannon Stocker |

A representation gap

Stocker, who is disabled and has children who are also disabled, felt called to write disability into picture books after noticing the huge gap in representation. “If there were more dialogue, if there were more books, if people with disabilities felt more seen and were more understood, then there would be more open conversation and acceptance,” she says. “And that’s what I want.”

Stocker, who is disabled and has children who are also disabled, felt called to write disability into picture books after noticing the huge gap in representation. “If there were more dialogue, if there were more books, if people with disabilities felt more seen and were more understood, then there would be more open conversation and acceptance,” she says. “And that’s what I want.”

Karol Ruth Silverstein (pictured right) was the 2020 teen book winner for her first novel, Cursed, portraying a ninth grader with juvenile arthritis, which Silverstein also has. Like Stocker, she had long dreamed about winning a Schneider award—even before she had written a book.

“Literally, it was announced, and I was like, ‘This is amazing; you’re going to recognize disabilities!’ I want to win that award; that’s the one,” Silverstein recalls.

Years later, Silverstein’s publisher, Charlesbridge, sent in Cursed to the 2020 Schneider committee for consideration. But Silverstein was convinced Erin Stewart would win in the teen category for her book Scars Like Wings, about a burn survivor. Silverstein prepared for disappointment. “You’re supposed to not even think about awards, and you definitely shouldn’t, like, put it on the calendar for when you might hear,” she says. “I do all the things you’re not supposed to do.”

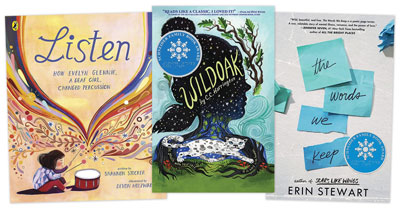

As it turned out, Cursed won that year, but Stewart went on to earn the 2023 teen award for her YA novel The Words We Keep, featuring characters grappling with mental illness.

|

2023 Schneider Award winners |

Judging process

Among the nine judges on the 2023 committee, all brought a perspective on disability, as is the case every year; whether they are disabled themselves, have family members who are disabled, and/or teach students who are disabled. Cochairs Susan Hess, a retired New York City public school librarian and seven-year committee member, and Mary-Kate Sableski, an associate professor at the University of Dayton and five-year member, are also judging for 2024. Unexpected benefits of serving on the committee, they say, are the deep, joyous friendships that are forged.

The judges use Goodreads to keep track of nominated titles. Publishers must submit books for the committee to consider them, and committee members often request ones they love that haven’t been put forward. Sometimes, the publisher still fails to deliver; such cases, Sableski says, are very disappointing to the judges.

Though the vote on the winning books doesn’t have to be unanimous, judges have often disagreed about which books should win, especially before honor titles were added. But, Sableski explains, “everyone’s willing to compromise.”

|

Left (left to right): 2023 winner Erin Stewart with her editor, Wendy Loggia; Middle (left to right): 2004 winners Andrew Clements and Wendy Mass, Allen Hale, a friend of Katherine Schneider’s, Schneider, and 2004 winner Glenna Lang; Right: 2004 winning books.From left: Courtesy of Erin Stewart; courtesy of Glenna Lang |

Looking ahead

Over the years, Schneider herself has been delighted by the winning books overall. The submission balance, however, still points to a dearth of representation. Former committee member Scot Smith, librarian at Robertsville Middle School in Oak Ridge, TN, says that while more books are being nominated now, picture books have a ways to go. For every picture book the committee receives, it typically gets three middle grade nominations.

There’s an accessibility issue, too. Picture books and graphic novels often are not issued as accessible audiobooks. Schneider isn’t part of the judging process, but she is frustrated when a book wins that she cannot read.

That happened with Wonderstruck by Brian Selnick, a 2012 middle school winner. “Being excluded doesn’t feel good, whether you’re five or seventy-five.”

Schneider was able to read the graphic novel eventually, after a national library service recorded it. But she maintains that publishers should make accessible copies of children’s books a priority. “If a book is going to be required in a school, and there’s a blind kid there, what are they supposed to do?”

There have also been critiques of the award within the disabled community, such as criticisms of recognized titles for inaccurately depicting disabilities or containing stereotypes. For example, Rules by Cynthia Lord, the 2007 middle school winner, tells the story of a nondisabled child’s frustrations with her autistic brother; some claimed it leaned into stereotypes of autistic people and dehumanized the brother. Others are also concerned by the prevalence of nondisabled authors whose works are honored by the committee.

Sableski and Hess would like to see more early chapter books submitted, along with fantasy that doesn’t magic away disability and books with a broader range of disabilities. Currently, they receive a lot of middle grade and YA submissions centering mental health, anxiety, learning disabilities, and parents with mental illness.

All the authors and judges emphasized the need to include disability within the broader definition of diversity. As Schneider says, “Disability is an equal-opportunity thing. Not an all-just-white-cis-folk kind of thing.” In a tally of the racial diversity of past Schneider winners and honorees, only 16 out of 72 recognized books were written and/or illustrated by

BIPOC and/or Latine creators.

Still, Schneider, the judges, and winning authors acknowledge many positive changes over two decades.

|

Seated left to right: 2023 winning and honored authors Gillian McDunn, C. C. Harrington, and Erin Stewart sign books.Courtesy of Erin Stewart |

All applaud how many current books feature characters whose disability isn’t the main focus, but they want to see more. The increase in mental illness representation is also welcome.

“To have the committee pick [The Words We Keep],” Stewart says, “and recognize anxiety and mental health diagnoses as disabilities, is a huge step forward for treating, recognizing, and talking about mental health.”

She adds, “The more we can look at these types of illnesses as chronic conditions, the more we can fight the stigma and get people the help they really need to live with these type of mental health concerns.”

To celebrate the 20th anniversary, past Schneider winners and their publishers will join the annual luncheon at the ALA conference in San Diego this summer. Hess and Sableski say one of their favorite parts of being a judge is hearing the surprise and elation from the winning authors.

“It’s been an absolute privilege” to serve on the committee, says Hess. And this month, with current and past winners gathered to celebrate, she expects to experience the thrilling emotions that come with every Schneider Award ceremony, complete with hugging, laughter, and tears.

Margaret Kingsbury is a Tennessee-based writer, editor, and teacher who is disabled.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!